Rethink the “post-script” as the model for reflection

The fourth writing program that I taught in was at a school that required every class to have a final exam.

What should a first-year writing final exam look like? I knew it wasn’t a typical “timed essay” graded on how well students plugged truisms into a standard five-paragraph form in their best Standard Edited American English.

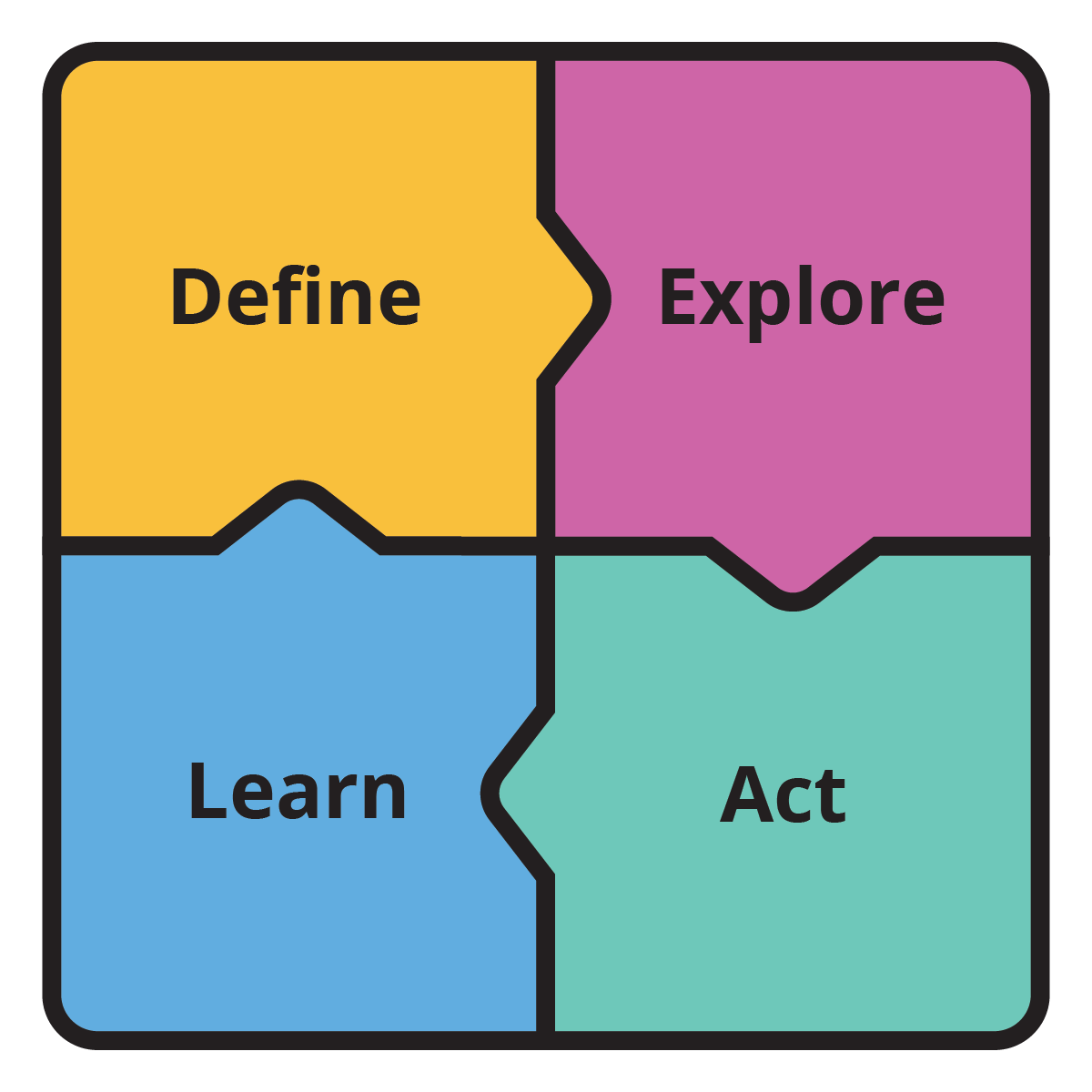

What I most wanted students to learn—what I wanted them to show me they could do a little better at the end of our time together—was to plan how to write the next document, one where I wouldn’t be there to support them. The exam I finally settled on, though I didn’t have specific language for it then, walked students through the four reflective practice moves that have become the part of RYW’s framework:

- Define the writing situation

- Explore possible options

- Act to implement your choices

- Look and learn from your actions

In that exam, students were presented with a “zero draft” of an argumentative essay from imaginary student Casey Bloom, and asked to write Casey a letter as a helpful peer reviewer. I asked them to

- tell Casey what they were already doing well and where some challenges might be

- explain some strategies that Casey might use for focusing, supporting, and structuring their argument

- recommend some specific steps that Casey should take next, and

- take a few sentences at the end to describe how the advice for Casey might apply to their own future writing

I loved reading my students’ responses! I was particularly cheered by the ways that students who would probably still describe themselves as “bad writers” (or who had been told this by others) rose fully to the occasion and gave Casey—and themselves—truly productive advice. Yet it was another decade before I started building this full-cycle reflection into all of my assignments.

The process-infused, product-focused writing class

For all that composition has spent half a century touting ourselves as a process-based field, we teach in a very product-based universe, and many of our courses reflect that. My courses reflected that for over twenty years, particularly in the ways that students see a course. What I saw was an infusion of process, a weekly set of steps encouraging experimentation, recursivity, and reflection. But students could see my product-orientation in my grade weights (where a semester’s worth of “process” work almost never crossed 15% of the final grade), and they could see it in my use of class time (which we used to practice semi-colons, MLA citation, and topic sentences, but never to practice rhetorical problem-solving in the middle of a paragraph). Mostly, they could see it in my writing priorities, which always included a reflective post-script, but always framed it as a task they would squeeze into the wee hours after they’d finished a “final” draft and before they came to class, having likely already forgotten about it by the time they polished off breakfast.

My journey back towards a process-focused writing class began with my students—and with peer review specifically. When I started treating student review of peers’ writing as a genre—with distinct moves I could teach students, with rhetorical expectations we could explore, with opportunities for practice and feedback, and with a new mantra of “reviewing benefits the reviewer”—I saw both why and especially how I could shift my priorities for it. Again, I watched students rise and flourish, moving beyond “Good Job, Jenny!” comments and punctuation corrections into a thoughtful community of writers.

The reflection-based writing class

Just as other textbooks help faculty center the study of genres or the study of writing as crucial content for a writing course, RYW is designed to center the study and practice of process, particularly reflection. “The writing process” isn’t just something we happen to do; it is a set of teachable concepts, learnable moves, practice-able skills, and improve-able sequences. Instead of saying “go reflect” or even “answer these reflection questions,” RYW helps students identify, evaluate, and take ownership of their working processes as writers.

The DEAL sequence in RYW Chapter 4 is at the heart of this focus on process. A cycle of reflective practice is not a new concept: it underlies the work of 20th-century education researchers like Albert Bandura, Donald Schön, and John Dewey. But teaching reflection and practicing reflection as a writer in a social learning environment require goals and guidelines, and DEAL provides a common framework—four basic moves—to enable progress. At any point in any writing task, a writer can pause and “DEAL with the situation”:

- Define the rhetorical or institutional context, the challenge, the need, or the goal at this point in the process. Students can use the language of rhetoric (audience, genre, exigence) or their own language (getting started, knowing how much is enough, fear of failure), as long as they aim for some terms that signify more productively than the common trio of writer’s block, grammar, or flow.

- Explore multiple options for choosing an action at this point in the process. RYW offers 9 threshold concepts and 9 composing moves; it describes 4 dispositions, 4 central purposes, and 3 stages of inquiry; and it offers 14 active reading strategies and over 70 practice exercises to help writers not just “do what they’ve always done” (or “go get a snack”) but consider what else their writing process could become in this moment.

- Act deliberately on their choice, with intention and agency, as a live experiment with the process of writing rather than by following a prefabricated checklist.

- Look at and learn from their experiments, with a goal of improving both the product and the process. Reflection can help writers articulate a revision plan for a current project/process, adapting to but not being ruled by feedback from peers or instructors. Reflection should also help writers assemble knowledge and strategies that they can adapt for future projects.

You might use RYW’s resources for small changes to reflective practice already embedded in your course: for instance, in framing your rhetorical context analysis assignments or post-script tasks with more precision. When you’re ready, though, RYW will support you in designing a course to substantially (re)focus on the study, exploration, and improvement of students’ reflective writing processes. It’s a good DEAL!